RESEARCH

How do we develop emotion understanding?

Emotion understanding—or the set of abilities related to determining the emotions of others—is crucial for the development of healthy social interactions. Emotion understanding allows us to respond appropriately to others’ needs, make predictions about social interactions, and even regulate our own emotional responses effectively. Indeed, research has shown that children who have better emotion understanding are rated as more socially skilled by their teachers, more likable by their peers, and are better able to navigate aggressive interactions. Likewise, children who have poor emotion understanding tend to be more aggressive, present with more behavioral problems and internalizing issues like anxiety, and demonstrate lower academic achievement.

Very broadly, our research program focuses on the development of emotion understanding, or the process by which infants and young children come to perceive, express, and regulate their emotions over the course of the lifespan.

How do we respond to threats in our environment?

Responding to threat quickly and efficiently is critical for survival. Indeed, when faced with the approach of a slithering snake or a dangerous drop-off, delays in responding can be costly, perhaps even deadly. But how do we learn what is safe and what is dangerous? How do we detect and respond to potential threats—dangerous animals, aggressive people, infectious diseases—in the world around us?

Because of the significant reproductive benefit associated with rapid identification of threatening stimuli, the most prominent theories propose that humans have evolved psychological mechanisms that facilitate the detection and subsequent avoidance of potential threat. These mechanisms are thought to detect cues in the environment that signal the presence of threat, and initiate cognitive and emotional responses that lead to avoidance behavior. For example, researchers have proposed that humans possess an evolved fear module that is activated upon contact with recurrent, widespread, and evolutionarily relevant threats like snakes, spiders, and threatening conspecifics; activation of this module is automatic, and leads to rapid detection and rapid fear learning for threatening stimuli. Behavioral immune system theory proposes that a similar set of mechanisms evolved to detect the presence of pathogens or infectious illness, automatically activating disgust responses that result in avoidance behavior. Although these and other similar theories differ in their specifics, they all assume that humans possess a specialized set of mechanisms for threat detection and avoidance that are universal, early emerging, and stable across individuals. However, until recently, very little developmental research had addressed this topic.

One line of our work investigates human behavioral responses to emotionally valenced stimuli—specifically to negative or threatening stimuli—and the mechanisms guiding the development of these responses. In one set of studies, we found that humans perceive the presence of threatening stimuli very quickly, and that rapid detection begins in infancy. However, these biases can be learned, they can change over the course of development, and may reflect a broad spectrum of individual differences. Further, in a second groups of studies, we found that avoidance responses to threats do not develop until later in childhood, and are dependent on learning. Other work builds on these findings to ask whether early perceptual biases for threat contribute to maladaptive avoidance behaviors, such as those associated with the development of fear and anxiety, and how children learn adaptive avoidance responses, such as avoidance of contagious people or contaminated objects. Altogether, our findings suggest that human threat responses are not singular or automatic: They are differential and complex, supporting flexible developmental trajectories based on both experience and context. By continuing to develop procedures that measure threat responses developmentally, and by establishing the developmental time course of these behaviors, we hope to create a broader theoretical framework for understanding how early developing biases for threat interact with everyday experience to create both adaptive and maladaptive patterns of responding.

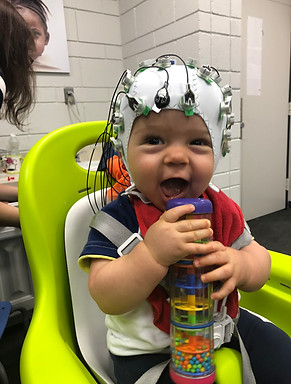

In one current line of work, we are studying the developmental trajectory of attention to emotional stimuli over the course of infancy to ultimately determine how early attention to various emotions, and specifically, signals of threat, play a causal role in the development of anxiety-related behaviors. Indeed, attention is a process by which infants themselves select the input they receive. If infants rapidly and preferentially attend to threatening or negative social information, this negative information may play a role in shaping their expectations about social situations, and ultimately, their social behavior. We have already observed that between the ages of 2 and 5, shy, or temperamentally fearful children more rapidly attend to social threats (i.e., angry faces) when compared to non-shy children (e.g., LoBue & Pérez-Edgar, 2014). In an ongoing collaboration with Kristin Buss and Koraly Pérez-Edger from Penn State University, we developed several new eye-tracking tasks that enable us for the first time to capture core components of attention in infants and toddlers, focusing on the relations between attention and negative affect (LoBue et al., 2017; Morales et al., 2017; Pérez-Edgar et al., 2017). In the NIH-funded Longitudinal Anxiety and Temperament Study (LANTS), we are employing a multi-method longitudinal approach, collecting data at five time points (4, 8, 12, 18, and 24 months) using our new eye tracking tasks coupled with a rich behavioral battery to measure negative affect. We will also assess known biomarkers (i.e., resting electroencephalogram [EEG] activity, and respiratory sinus arrhythmia [RSA] during challenge), and parental characteristics (e.g., anxiety, depression, psychosocial stressors) known to increase risk for anxiety. We are using these variables to predict behavioral inhibition, or social withdrawal—the most significant known predictor of social anxiety—at age 2.

To read more about LANTS, this paper describes its aims and measures:

Pérez-Edgar, K, LoBue, V., Buss, K. et al. (2021). Study Protocol: Longitudinal Attention and Temperament study (LAnTs). Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 679. Download PDF

How does neighborhood affect the way we perceive and learn about threat?

Neighborhood environments play a critical role in shaping our social and emotional development as well; neighborhoods determine the type of people we can interact with, where we can go, and what resources we can access. Further, neighborhoods can create sources of threat, such as community violence, which we define as intentional acts of violence (e.g., fighting, weapon violence) committed in public areas (Hunt & Tomlinson, 2018). Research demonstrates that community violence exposure is linked to various adverse socioemotional outcomes, such as anxiety, depression, and aggression (Cimolai et al., 2021; Turner et al., 2019; Quimby et al., 2018). While research has linked community violence exposure to the development of socioemotional outcomes, less is known about the mechanisms that drive this relationship.

In another line of work, we are examining how exposure to community violence shapes the development of attention to various types of threats (e.g., angry faces, snakes, and guns). Research suggests that attention to threat can be a marker of anxiety vulnerability and elevates anxiety (Abend et al., 2018; Fox et al., 2010). Using eye-tracking, fMRI, and behavioral tasks, we are considering the differences in attention to threat for those exposed to community violence, and if this attention bias relates to emotional outcomes like anxiety, and how exposure to community violence shapes emotion regulation abilities (Gross, 1998).

How do children learn about illness transmission?

In a newer ongoing line of work, we are expanding previous research on the perception of threatening animals and social threats to examine how children behave in the presence of a biological threat or contagious illness. Young children are exposed to a countless number of germs every day—in the air or on surfaces they encounter (e.g., floor and objects), on their toys, and on the floors that they play on. With more opportunities to contact germs and a less developed immune system, children are particularly vulnerable to getting sick. Researchers have consistently shown an interest in what children know about illness. Using verbal reports and child interviews, researchers reported that around the age of 5, children are beginning to reason about illness and contagion. However, although knowing how we get sick is important for development, it does not necessarily translate to behaving adaptively when confronted with it.

To explore this topic, we have previously investigated how exactly children behave when faced with the possibility of getting sick. In a preliminary study, we were most interested in understanding and examining when children spontaneously avoid contact with sick individuals and contaminated objects. We recruited a group of local children between 4 and 7 years old to play with the toys in two experiments, one of which was “sick” and the other was not. After assessing children’s knowledge of contagion, we discovered that overall, older children (aged 6 and 7) avoided proximity to and contact with the sick experimenter and their toys. However the best predictor of avoidance was not age, the ability to make accurate predictions about whether someone will get sick based on prior risky health behaviors (Blacker & LoBue, 2016). Thus, knowledge about illness transmission was the key factor in whether or not children would behave adaptively in the face of getting sick, even in our youngest children.

Based on this preliminary work, we are now examining how providing preschool-aged children with different kinds of information about illness transmission will lead to increases in both causal knowledge about illness transmission and behavioral avoidance of contaminated objects. In an ongoing NSF funded study, we are taking a longitudinal mixed-method approach centered around a storybook intervention model to investigate how and when children learn and develop the causal knowledge necessary to display adaptive health behaviors about contagion. In the study, children are randomly assigned to hear a storybook about illness that is designed to teach them about the causal mechanisms that drive illness transmission, a storybook about illness with no causal information about transmission, or a storybook unrelated to illness. We test children’s knowledge about illness transmission before and after the storybook reading and at a 3-month follow-up. Second, we assess the behavioral impact of the storybook by using an illness avoidance task to examine children’s behavior toward a potentially contaminated toy. Further, we obtain records of absences from the children’s classrooms and information about children’s health behaviors at home from the time of the storybook reading to the 3-month follow-up. Finally, will use these additional behavioral data to build an epidemiological model of the school(s) themselves that assesses the potential magnitude and sensitivity of the impact of our storybook reading on broader community health.

What is the input infants and young children use to shape their emotion understanding?

There is substantial debate about how we develop emotion understanding over the course of the lifespan, but classic theories of emotion have had a significant and long-lasting impact on the way we study emotion understanding for decades. According to these perspectives, there is a basic set of emotions—including anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. These emotions are universal and reflect evolutionary adaptations to specific environmental challenges, and each emotion has a distinct physiology and brain circuitry (Ekman & Cordaro, 2011; Izard, 2007; Panksepp, 2007). Perhaps because of the intuitive nature of this view, its popularity has caused many social scientists to ignore the role of the environment in emotion understanding, and most importantly, how input from the world around us shapes emotion understanding over time. Indeed, the assumption that most of our basic emotions are universal leaves little space for variation based on culture and context.

In a newer line of work, we are taking steps to fill this gap in the literature by examining the emotional input that shapes children's emotional understanding. In one group of studies, we are examining the types of language parents use to talk to their children about animals that are highly feared, like snakes and spiders. Previous research suggests that the vast majority (89%) of intense childhood fears comes from negative input, either from parents or from media (Ollendick & King, 1991). Thus, we are currently conducting several studies investigating whether input from parents could account for some of the higher prevalence of snake and spider fears compared to other fears among children and adults. Across several studies with preschool-aged children and their parents, we are finding that parents provide less positive and more negative information about snakes and spiders than they do about other, equally threatening animals (Conrad, Reider, and LoBue, 2021). Further, we found parents' negative emotion language is related to how fearful their children are of snakes and spiders (Reider et al., 2022).

In a related line of work, we are also examining the natural emotional input infants are exposed to in their everyday environments. In NIH funded study, we are coding several existing datasets for emotional information from parents' faces and language to describe the typical emotional environment of a group of infants between 6 and 17 months of age. In a second study funded by NSF, we are collecting our own data longitudinally from 120 infants at 3 time points—at 6, 9, and 12 months of age. At each time point, we are capturing (via a head-mounted eye tracker) emotional input during infants’ interactions with their caregivers. Infants are also completing four classic emotion perception tasks at every time point, each of which taps into a different aspect of emotion perception and understanding. Caregivers complete questionnaires that assess aspects of their functioning and home environment. Using all of these data, we will first describe infants’ exposure to emotional input in the first year and a half of life. Next, we will investigate how variations in caregivers’ emotional inputs predict infants’ subsequent performance on the emotion perception tasks. Finally, will examine the active role infants play in curating emotion knowledge, by expressing affect themselves and then by observing contingent responses from their caregivers.

The Child Affective Facial Expression Set (CAFE)

Emotional development is one of the largest and most productive areas of psychological research. For decades, researchers have been fascinated by how humans respond to, detect, and interpret facial expressions. Most research on face perception has relied on controlled stimulus sets of adults posing various facial expressions. Although these sets provide an easy, controlled way of examining responses to human facial expressions, they are limited in that they only represent emotional expressions in one specific group, namely Caucasian adults. At the Child Study Center, we are currently working on a new stimulus set of emotional facial expressions into the domain of research on emotional development—The Child Affective Facial Expression set (CAFE). The CAFE set is unique and significant to the field for several reasons. Primarily, instead of featuring photographs of adults posing various facial expressions, it features photographs of 2- to 8-year-old children. To date, very few stimulus sets feature children posing facial expressions, and none have featured children as young as preschool age. The stimulus set is also racially and ethnically diverse, featuring Caucasian, African American, Asian, Latino (Hispanic), and South Asian (Indian / Bangladeshi / Pakistani) children. In an NSF funded project, we validated the CAFE set and it is currently available for free to the scientific community (LoBue & Thrasher, 2015).

For more information on how to obtain the CAFE set, visit the CAFE page.

The Rutgers Mobile Maker Center (MMC)

Photo by Elizabeth Lapidow

In collaboration with Elizabeth Bonawitz and Pat Shafto, we are currently working to build the Rutgers-Newark Mobile Maker Center (MMC), a fully mobile lab that can be brought to local science museums, parks, play centers, zoos, and libraries to study children’s learning and to bring science directly to the community. The Rutgers-Newark MMC is now fully constructed, and we hope to use it to collect data in a new location this fall.